Many of us tech folks are overflowing with business ideas, from local solutions to our close circles’ problems to ambitious global-scale projects. But it’s also accompanied by an infinite uncertainty that blocks us from making the first step. Knowing that 9 out of 10 startups eventually die (more depending on the look-back window), it’s pretty easy to stay frustrated and never act.

My name is Dmitrii, and I have been building tech products for almost 10 years in a C-level corporate position and as a startup co-founder. I’ve launched and scaled products in EdTech and eCommerce and multiple regions and countries, including, but not limited to, Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Brazil, Mexico, Israel and the United States. And I’ve managed to collect failures and successes in most of them.

I will share my perspective on how you can structure and assess your ideas to focus on the most promising scenarios, hopefully giving you an increased chance to avoid repeating my mistakes.

Please consider that it’s not scientific research, and most items are simplified for easier perception. It’s tailored with VC-model startups in mind and primarily focuses on B2C products. The acquisition part is less applicable for B2B, where your sales force matters more. Any approach works if you’re building a business for an additional $10-20k monthly personal income.

Step 1. Idea / product type definition

Let’s look at the basics. What kind of products are there anyway?

We may structure them into 3 types:

-

Painkillers 💊 – products that drastically change the approach to solving the problem at the time of the launch. The competition in their segments was with the old ways of doing things, Uber vs classic taxis; Google.Maps with offline maps and standalone hardware; Skype with expensive international phone calls.

They had many barriers and tough competition, but they followed the Blue Ocean Strategy, which means launching in an uncontested market segment and disrupting it with tech innovation. It’s called a painkiller because the meds market is quite an accurate analogy – you struggle hard and/or frequently without having that solution available. Now, each of these products is in a red shark-tank market.

-

Vitamins / Delighters 🍏 – in 2024, around 99% of startups fall into this category. They substantially improve the user experience of competition or predecessors but do not actually change the core. Chrome won browser wars with a very close solution to Explorer, Opera, and Mozilla, but it was much faster, which meant so much that eventually they became #1. Zoom did the same with Skype, providing the audience with better (still not perfect) UI, connection quality and accessibility for larger groups.

-

Dopamine cycle 🔁 – you know them all: socials with dopamine hooks to keep you scrolling and observing content, games with repetitive loops and microtransactions, mostly with social elements. Your economics is based not on the value of solving a substantial customer problem. Instead, it is driven by the fun and pleasure loops, making it addictive. Don’t get me wrong, those products are amazing yet ethnically ambiguous. Great business if you can build it.

I have to mention that there’s another type of the product – infrastructural or technical. You can look at what OpenAI builds (i.e. their API) from that perspective. However, depending on the use case, these products might fall into one of the 3 categories listed above.

Note. Facebook might be considered a painkiller on its initial launch, yet the model itself does fit into the latter category

Step 2. Cost groups per product type

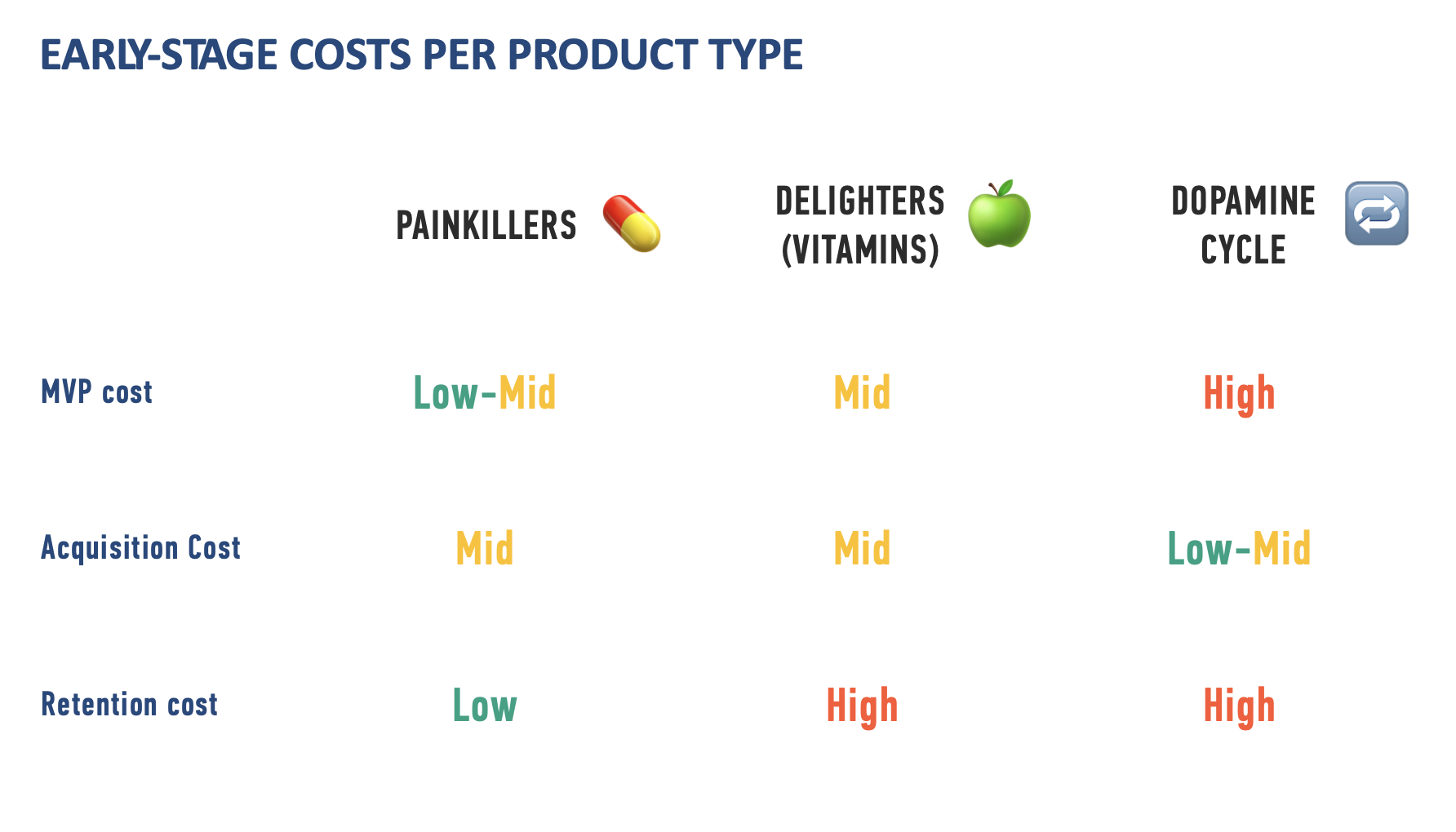

Ok, got it, so what? It will define how most likely you will perform in your first 1-3 years of a startup lifecycle. Here’s roughly how it relates:

Let’s look at this dimension:

-

Cost for Painkillers 💊 – MVP cost is usually low to mid, if the problem is not resolved and THERE IS a technological possibility. In most cases, the first tech to create substantial value can be built quickly. The first ride-hailing app was easy to build on new smartphones, multiple AI SaaS solutions are now growing on GPT API like mushrooms, and some are actually solving substantial problems like huge costs for legal teams, etc. You need to invest in market education to find new ways of doing things. The acquisition is not cheap, but it gets better over time since customers are ready to share, and they stick pretty tightly.

-

Costs for Vitamins / Delighters 🍏– you already have to be better than an existing solution, so it’s re-create and surpass your predecessor. You don’t need to educate the market, but you’ll have to explain how you are better and bear the switching cost. Your retention costs will most likely be high due to competition with other solutions if you don’t manage to build great viral and dependency cycles.

-

Costs for Dopamine cycle 🔁 – well, to get people hooked, only the content is not enough. You will need great algorithms, creators (if UGC model), moderation and regulation. People are ready to share and try new stuff, but the attention market is a blood bath. These products relate to the network effects, so they only start to pay back after surpassing the critical user base. Be ready to raise tons of capital, not even speaking about the monetization models that usually are ads-based and become available to millions of active users. It’s usually a 3-sided marketplace with users, creators and sponsors. But if you’re an expert, you can always try.

Note that it doesn’t consider your business model and costs relative to the same model type competition on the market, but it can vary highly within one bracket.

Step 3. Market Estimation

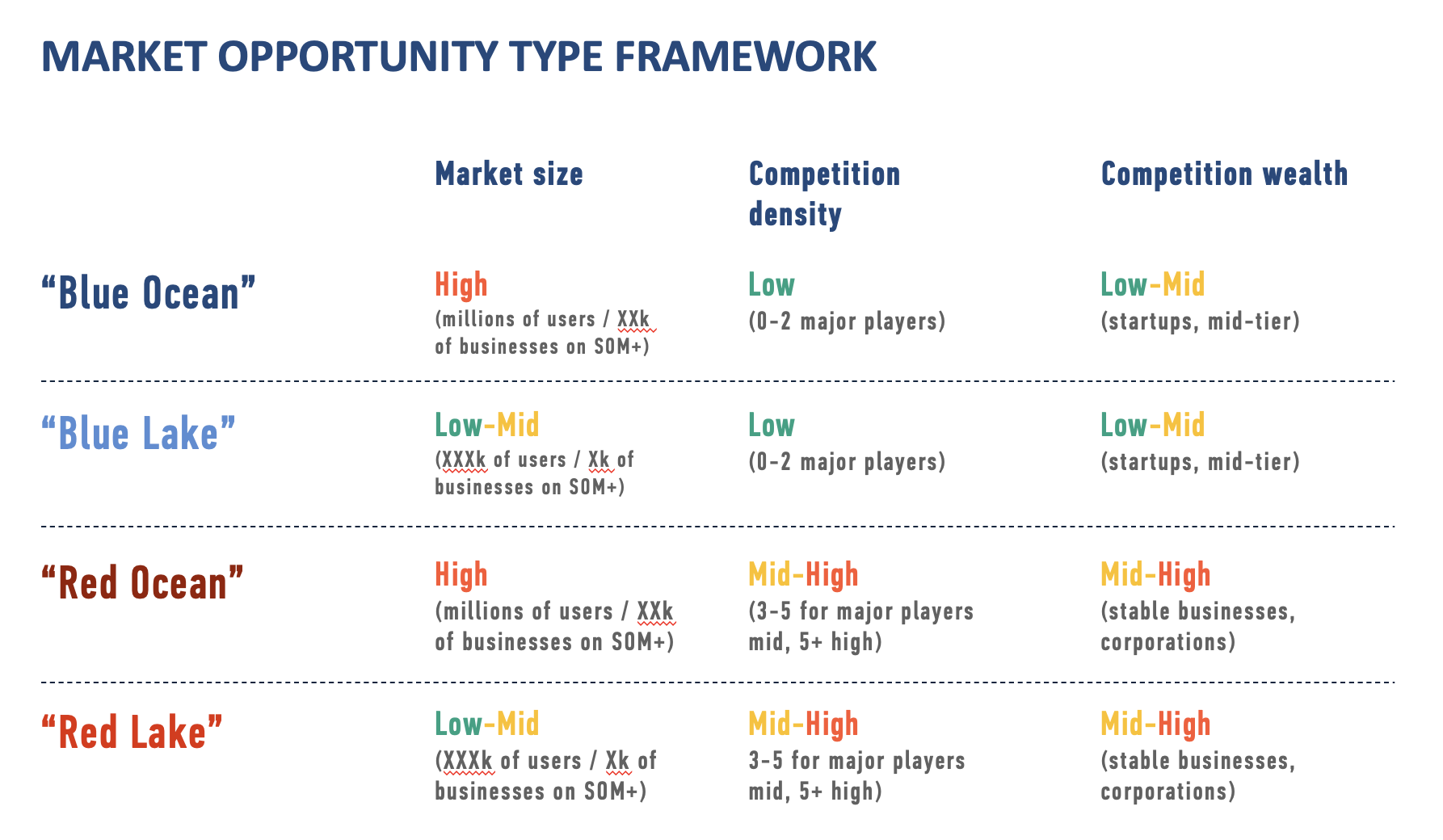

That was a spherical horse / cow in vacuum example of how it depends on the product type. Now, let’s make it a bit more complex and add a market layer. The earlier mentioned Blue Ocean vs. Red Ocean strategy is a solid framework, but it doesn’t take into account market size differentiation and its drastic impact on tech product launches.

I propose adding another layer to assess the competition per potential user.

- The typical market size estimation – TAM/SAM/SOM framework. I won’t get into details, but you can easily check it now here on Antler.

- The assessment logic here is pretty simple: the bigger your market, the easier it will be for you to kick off. Reaching X% in the broad segment will always be more expensive in any resource than 10X% on the smaller one, but it may bring you more money and users. It works on all ends – finding respondents for discovery, acquisition cost in performance channels (I will give some examples later), risks of experiments and cumulative retention or LTV baseline you can stack.

- Competition density affects all the same criteria above, yet no competition might be worse than some. If the market is new, you will share your customer education costs with other players, and you will all move faster. In the old market with many players, they will compete in advertising auctions, making every bid and new user more expensive. This can go exponentially and drastically affect your viability.

- Competition wealth / capital – assess with whom you compete. Obviously, you can outrun similar-sized companies or startups, but if you compete with a tech giant, you most likely won’t be able to outplay them in customer acquisition. However, you can build your strategy around acquisition. This is a separate topic and you should initially design your startup to that prospective possibility.

There’s no universal scale, it’s again relative to the market, but let’s try to put it all together, we will label smaller markets “lakes” and bigger markets “oceans” correspondingly.

Step 4. Merging frameworks

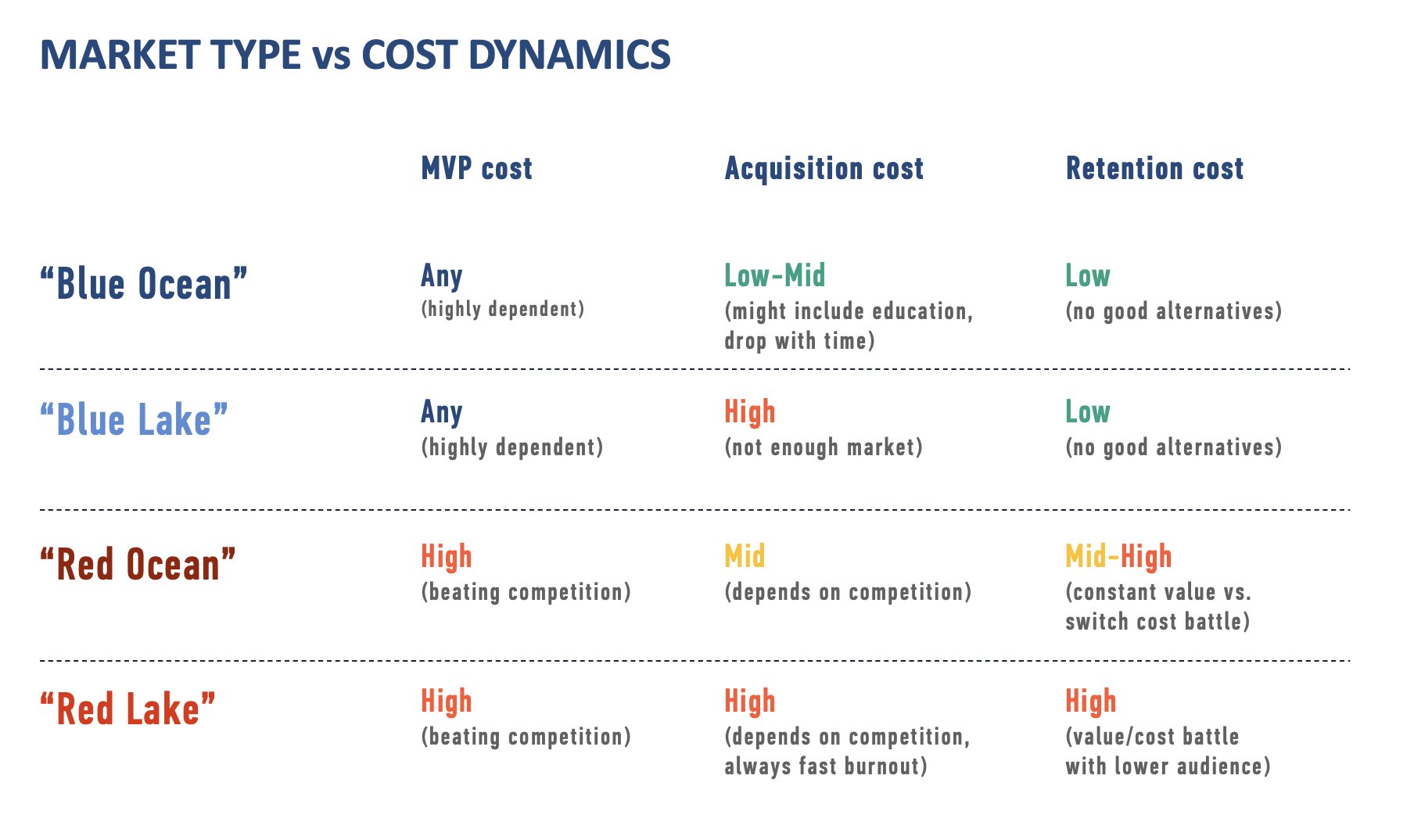

In Step 2, we discussed general relative costs per product type, which also highly depend on the market structure!

Why? Due to the scaling cost rules and how the most commonly used acquisition channels are built (auction-based models). This can be referred to as “product channels fit” or simply asking, “Can I scale it to the target level with the instruments available to me?”

So, if we merge our matrix of costs and market types (I hope I am not losing you yet 😅), we might get something like this:

If rephrasing the table content:

- On a larger market Your acquisition costs are lower. If you use performance marketing – Google, Meta, and YouTube paid ads, you will have enough audience to reach and segment. You can build look-a-like groups and get decent bids. Your early adopters and core target audience will be covered and burned down slower, so you have a run rate to kick off. The same rules work for influence marketing and referral channels, but slightly smoother.

- If you fail initially, you have enough of a market to iterate and scale when you find a working communication strategy.

- If market is competitive in budgets – your bids will grow proportionally, but it still might have enough room for growth.

- But when people start seeing your traction, the competition will appear as if it did not exist before.

- On a smaller market Fast-pace audience burnout (burn-down?) → the audience will quickly switch to less relevant → your marketing bids go higher.

- Simply not enough audience to train the algorithm cycles, low quality targeting.

- If you fail with communication strategy or positioning, you might not have enough audience left to scale up.

- If market is competitive in budgets – your acquisition and retention costs will go wild.

- But – if you managed to win a decent market share, might not be interesting for any competition to enter.

Step 5. Let’s put it all together

A short recap of what we did ✍️:

- Conducted a market / customer problem research and defined for ourselves what type of product we are creating

- [Most likely] qualitatively assessed our relative costs that might be associated with production, acquisition and retention

- Checked the market size by any available means (keep in mind that for blue types of markets, the estimate will be assumptions-based and vague anyway) and our competition power (use ads analytics on Facebook, Google Ads tools, services like SEMrush, SimilarWeb, etc.)

- We are here

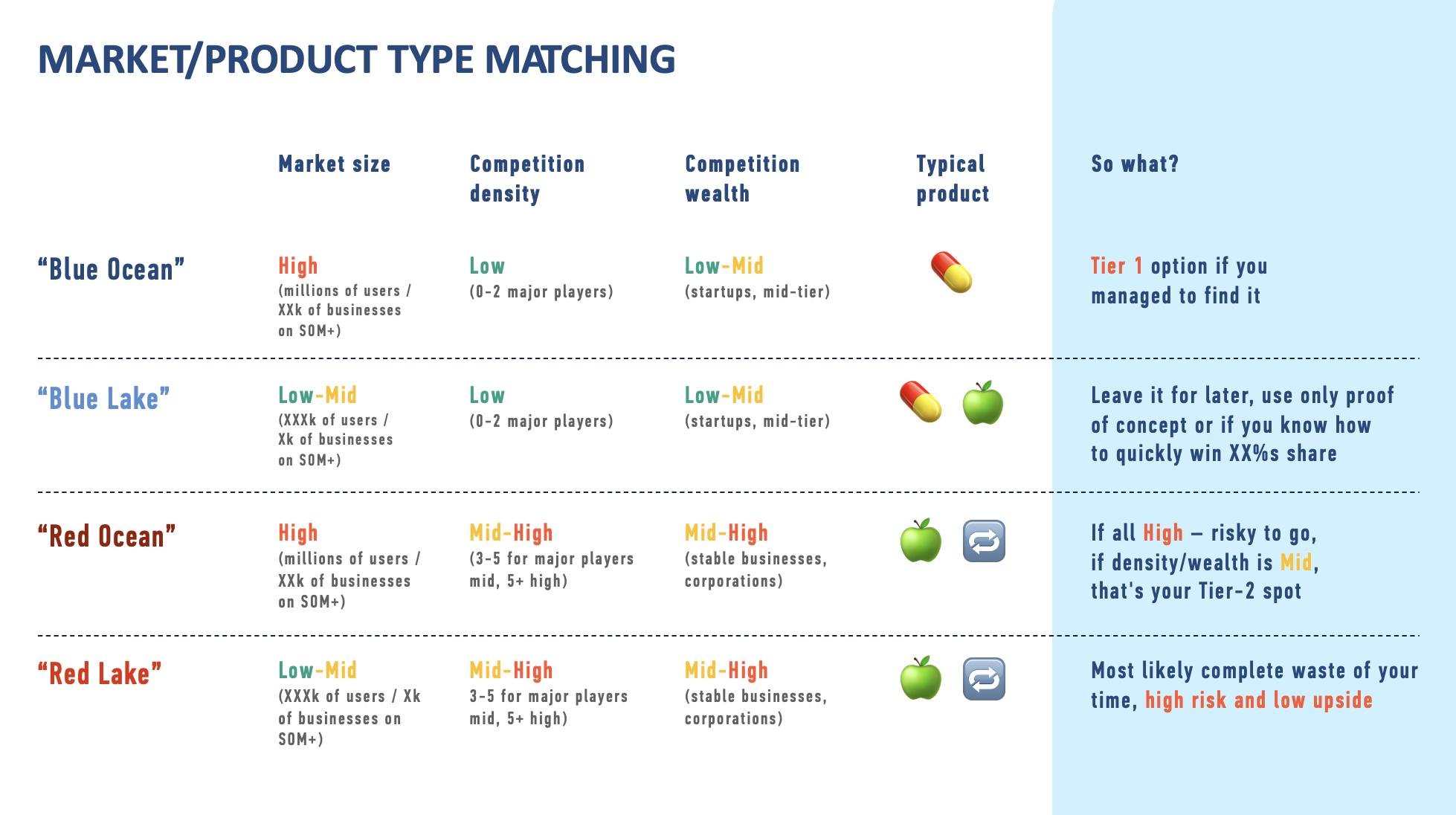

So, if you have a few ideas and can gather enough qualitative and quantitative data to drag them through the stage above, congratulations— you can now weigh your chances!

But before I share with you my final approach structure – this is how it was for me for the 1st C-level / founder experience.

Spoiler – I f*cked up!

We launched in a Blue Lake type market with Vitamin type product (supplementary education) without knowing the audience well. We didn’t have any segment competition, but we overestimated the market by thinking it was an Ocean, so the targeted audience for the product was much more narrow (well, you can actually check it on the interview stage without any product)

- We ACTUALLY built a product with a good PMF – fantastic retention, high stickiness, great reviews and NPS

- BUT we didn’t find a product-channels fit. We nailed performance and influence marketing quality, but the CAC (acquisition costs) grew faster than LTV with new product/feature launches, it was a severe audience burnout issue

- We burned out a significant audience share before getting to a working comms

- We spent an enormous amount of money on customer education on the offering

- Our acquisition economics became worse and worse with scale

What happened next?

→ → → We used the same tech to pivot into the Red Ocean market segment, but we knew that we could be more attractive in content, product quality and pricing in the long run. And it actually worked despite taking significantly higher risks.

Our CAC dropped 5 times, LTV grew 20 times, retention costs became higher, but manageable, so we finally hacked the growth. If I were about to start anew, I would first make my money in a big market with warmed-up audience, rather than going “the easy way”.

This rule was later successfully applied to every market by industry, geography we launched, and all the tech companies I worked in/with, so I think it’s a solid baseline model.

So wrapping up the story, here’s the approach I recommend:

- Tier-1. Try to find the Blue Ocean and disrupt big, as in any startup founder’s dream

- If not, find your differentiation point and go make some cash in a big, competitive Red Ocean market

- If you know your segment well, try to get XX% (double-digit) of uncontested smaller market

- If you still want to try – sure, spend your money and time in a small contested market. Experience is also valuable 😉

Eventually, every case is individual. There are as many approaches as founders and startups, but I hope you can at least get additional lenses to look at your ideas. Aside from that, it might save you some nerve cells.

What’s your experience? Have you fallen into the same traps or beaten it regardless of all the complications? Where does your project or idea stand in that structure?

Let me know in the comments, or reach out to me on Meander, where I conduct mentorship sessions with early-stage founders and product managers.

Cheers, and have a good one!